What is the Zone of Proximal Development theory?

The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is one of the most important ideas in educational theory and a key part of Lev Vygotsky’s social constructivist approach to learning. Vygotsky, focused on how social interaction, communication, and culture shape a person’s learning and development. He believed that human beings learn best when they are supported by others and that learning happens first on a social level, before it becomes something that an individual can do alone.

For students studying early years education, Vygotsky’s theory provides a valuable framework for understanding how young children acquire new skills, develop understanding, and build confidence through interaction with adults and peers. It reminds practitioners that learning is not a solitary process, rather, it is something that happens through relationships, dialogue, and shared experiences.

Vygotsky’s View of Learning and Development

Unlike Jean Piaget, who saw children as “little scientists” developing their understanding through exploration and discovery at their own pace, Vygotsky believed that learning could be accelerated and deepened through social support. He agreed that children have natural stages of cognitive growth but argued that these stages can be extended when children are given the right kind of help.

Vygotsky saw learning and development as interconnected processes. Development provides the foundation for learning, but learning can also lead development forward. For example, a child might not yet be developmentally ready to write a full sentence independently, but through shared writing activities with an adult, such as dictating a sentence while the adult writes it down, the child begins to understand how spoken words can be represented in writing. This guided experience helps prepare the child’s thinking for future independent writing.

The More Knowledgeable Other

At the heart of the ZPD is the idea of the More Knowledgeable Other. This refers to anyone who has a greater level of knowledge, skill, or understanding in a particular area than the learner. The More Knowledgeable Other could be a teacher, practitioner, parent, peer, or even an older sibling. What defines the More Knowledgeable Other is not their age or authority, but their expertise or experience in the specific task.

For instance, in an early years setting, a practitioner may act as the More Knowledgeable Other when teaching a child how to use scissors safely for the first time. They demonstrate how to hold the scissors, guide the child’s hand, and give verbal cues such as, “Thumb goes in the small hole, fingers in the big one.” Over time, as the child becomes more confident, the practitioner offers less physical help and simply provides encouragement, until the child can cut independently.

However, the MKO does not always have to be an adult. A peer who has already mastered a particular skill can also take on this role. For example, one child might show another how to build a tower with blocks that doesn’t fall over by explaining, “You have to put the big ones at the bottom.” This peer interaction allows both children to learn, the one giving help reinforces their understanding, while the one receiving help gains a new skill through observation and guidance.

This process of gradually reducing support as the learner becomes more capable is called scaffolding. Scaffolding involves adjusting the amount and type of assistance based on the learner’s progress, ensuring they remain challenged but not overwhelmed. In the early years, scaffolding might include demonstrating, modelling language, asking guiding questions, or offering prompts and encouragement.

For more information on Scaffolding, why not try:

The Three Zones of Development

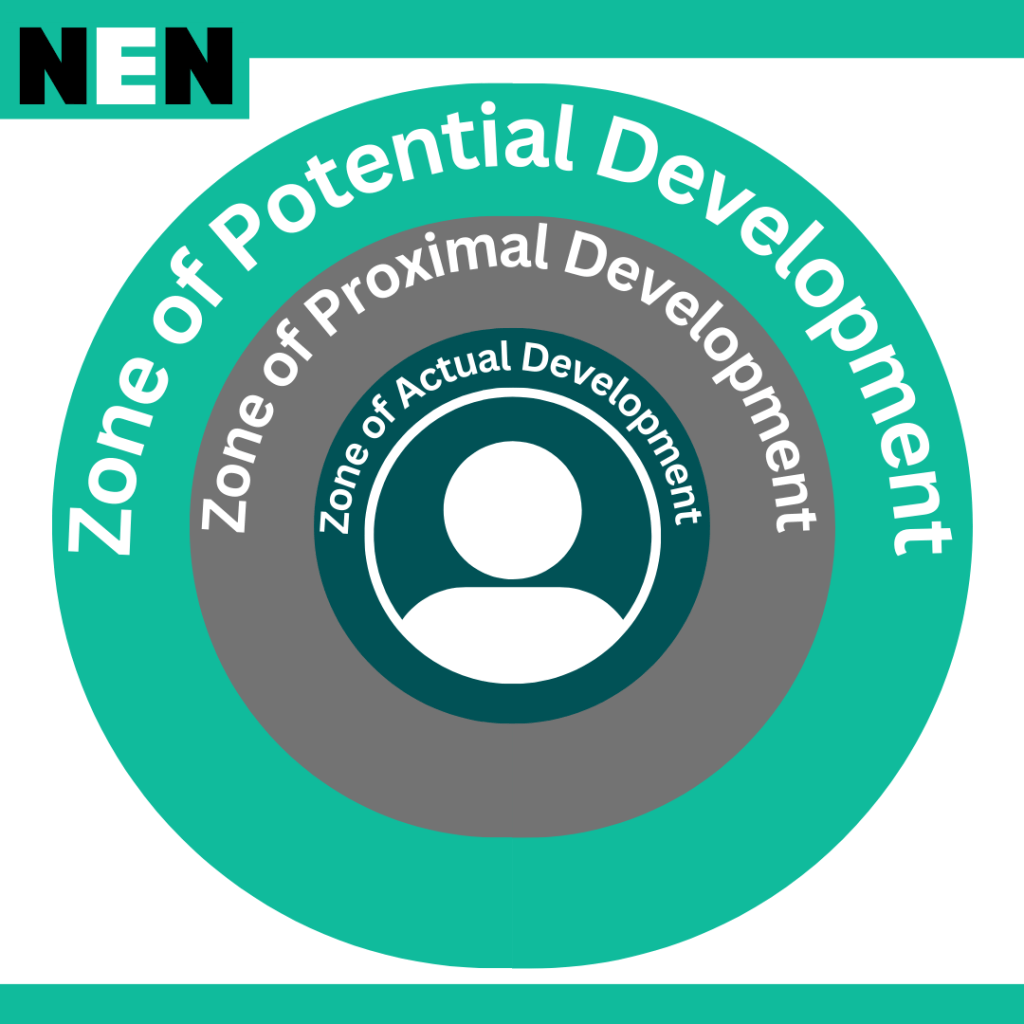

Vygotsky described learning as taking place within three overlapping zones that represent different levels of ability and independence:

The Zone of Actual Development

The Zone of Actual Development refers to what a learner can already do independently without any help. It includes the skills, knowledge, and behaviours they have already mastered and can use confidently.

For example, a child who can count to ten unaided, recognise basic colours, or put on their own coat is operating within their Zone of Actual Development. This zone represents their current level of competence. However, to continue developing, the child must be encouraged to move beyond what they can already do. This is where the Zone of Proximal Development becomes important.

The Zone of Proximal Development

The Zone of Proximal Development is the most dynamic area of learning. It represents the gap between what a learner can do on their own (the Zone of Actual Development) and what they can achieve with help from a More Knowledgeable Other.

Vygotsky defined this as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem-solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978).

This means that within the ZPD, the learner is working on tasks they cannot yet complete alone but can succeed in with guidance and support. Over time, as understanding and ability grow, these tasks move into the learner’s Zone of Actual Development.

For example, a child might not yet be able to write their name independently, but can do so when a practitioner helps them by saying each letter aloud and showing how to form it. The practitioner’s guidance enables success in the task, an achievement that would not yet be possible without support.

The ZPD is where true learning takes place, because it is where the learner is being stretched, not doing something too easy (which can lead to boredom) or too hard (which can lead to frustration), but something just beyond their current ability.

The Zone of Potential Development

The Zone of Potential Development includes tasks or skills that are currently beyond the learner’s ability, even with support. These might require more advanced cognitive, physical, or emotional development before the learner is ready to attempt them.

For instance, a two-year-old child may not be able to understand the concept of subtraction, even if an adult tries to explain it. The skill is too far beyond their current developmental level. However, as they develop their understanding of numbers and begin to perform simple addition, subtraction will eventually move into their Zone of Proximal Development.

This gradual progression demonstrates the spiral nature of learning in Vygotsky’s theory. What begins as the Zone of Potential Development can later become the Zone of Proximal Development, and eventually, with practice and experience, become part of the learner’s Zone of Actual Development.

Cultural Understanding and Learning

Vygotsky also placed great importance on the role of culture and social context in shaping how individuals learn. He argued that learning is not just about acquiring facts or skills in isolation but about developing understanding within a cultural framework, the shared values, beliefs, and practices of a community.

This idea is closely linked to what modern educators call cultural capital, the knowledge, experiences, and understanding that children gain from their families and communities, which help them make sense of the world and connect new learning to familiar experiences.

For example, a child who regularly helps their family in the kitchen may find it easier to learn about measuring and counting during a cooking activity in the setting. They already understand why measuring is important because they have seen it used in real life. Similarly, a child from a family that values storytelling and reading at home may develop strong language and literacy skills earlier, as they can relate new learning to their cultural experiences.

Vygotsky believed that the More Knowledgeable Other plays a key role in helping learners link new knowledge to their existing cultural understanding. Practitioners can do this by connecting learning to children’s home experiences, using familiar examples, or celebrating cultural traditions within the setting. This helps children attach meaning and relevance to their learning, making it deeper and more memorable.

For more information on Cultural Capital, why not try:

The Natural Rate of Development

While Vygotsky believed that effective social support could accelerate learning, he also recognised that all individuals have a natural rate of development. He acknowledged that some skills can only be learned effectively when a person reaches an appropriate stage of readiness.

For example, a child who is not yet physically able to control a pencil may struggle to form letters correctly, even with help. In this case, the role of the practitioner is to provide experiences that build the child’s fine motor skills, such as threading beads or using playdough, before expecting them to write.

This understanding highlights the importance of developmentally appropriate practice. Educators must recognise when a child is ready to move into their ZPD for a particular skill and when they need more time to develop foundational abilities.

Vygotsky’s view aligns partly with Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, which describe predictable stages of intellectual growth. However, while Piaget saw these stages as fixed and universal, Vygotsky believed they could be influenced by social and cultural factors. With the right guidance, children can often reach higher levels of understanding earlier than expected.

The Role of Language in Learning

Language was central to Vygotsky’s theory of learning. He believed that language is the main tool for thought and communication, allowing individuals to organise, express, and develop their ideas.

Vygotsky argued that language and thought are closely connected, when children engage in dialogue, they are not only communicating with others but also learning to think for themselves. He suggested that learning first occurs through social speech, talking with others, and later becomes inner speech, thinking silently in words.

For example, when a child talks aloud while solving a puzzle (“This piece goes here because it’s the same colour”), they are using self-directed speech to guide their thinking. Over time, this speech becomes internalised, allowing them to plan, problem-solve, and reflect silently.

Practitioners play a vital role in promoting this development by engaging children in meaningful conversations, asking open-ended questions (“Why do you think that happened?”), and encouraging children to explain their reasoning. Through these interactions, children learn the language of thinking, words such as “because,” “if,” and “maybe”, which support their cognitive growth.

Applying the Zone of Proximal Development in Practice

In early years settings, understanding the Zone of Proximal Development helps practitioners plan activities and interactions that are challenging yet achievable. It encourages adults to observe children closely, identify what they can do independently, and then offer just the right amount of support to help them take the next step.

For instance, when supporting early writing, a practitioner might first demonstrate how to form letters, then encourage the child to trace over them, and finally invite the child to attempt writing alone. Each stage represents movement through the Zone of Proximal Development.

Similarly, during play, a practitioner might notice that a child can stack three blocks but struggles to balance a fourth. By suggesting, “What if we put the big block at the bottom?” and modelling the action, the practitioner provides the scaffold that helps the child succeed. Over time, the child internalises this strategy and uses it independently.

In this way, the Zone of Proximal Development is not just a theoretical concept but a practical guide for supporting responsive and effective teaching. It encourages practitioners to see themselves as co-learners and facilitators, working alongside children to build understanding through shared experiences.

Reference

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.